As a child in the UK when my mother referred to ‘broad bronzed Anzacs’ the expression mystified

me both because I had no idea what an Anzac was and because my transplanted

Australian father’s physique, while undoubtedly broad at some points, sported a

pallid dermis with no trace of metallic sheen.

When later we moved to Australia and lived in Puberty Blues land I began

to ‘get’ the bronzed bit and realised that Max Dupain’s prone 1937 ‘sunbaker’

epitomised the type visually (despite actually being an Englishman). And in

hindsight, my Uncle Eddie’s insistence that a hot shower was the best cure for

sunburn certainly captured something of the masochistic spirit that can imbue

Anzac commemorations.

|

| Max Dupain 'The Sunbaker' |

My real introduction to the Anzac legend came in first year

high school when my class was asked to write a dramatic account of scaling the

cliffs at Gallipoli. I don’t recall

being given any context for the event but, for one raised on Enid Blyton and

John Buchan, a total ignorance of Australian history was no obstacle to writing

a piece of wonderfully mawkish jingoistic prose. I was awarded a prize for my efforts by the

Caringbah RSL!

Continued immersion in Sutherland Shire society did not

bring improved knowledge of World War 1 and Australia’s participation in it (let alone New

Zealand’s, but that is for another post) or even much awareness of the annual Anzac

Day march itself. I was however

introduced to the vital aspect of mateship that involved my dad and uncle (my

uncle was at least an ex-soldier) disappearing to the RSL for the day on April

25th and returning completely pissed. Soon I renounced Blyton and Buchan and

embraced Alan Seymour’s ‘The One Day of the Year’ with every fibre of righteous

indignation in my being, conveniently overlooking its message of compassion for

those who clung to their military service as the sole source of pride and

meaning in otherwise empty lives.

|

| Theatre On Chester's poster for their 2018 production of Alan Seymour's play about Anzac Day 'The One Day of the Year' |

Come the 80s and I had still not studied much Australian

history but had, through my Fine Arts course at uni, been exposed to the ‘making of a nation/cutting

the colonial ties’ view of our participation in WW1. Peter Weir’s 1981 film ‘Gallipoli’ was lauded for depicting the Anzac

experience through the stories of Archy and Frank, two athletic innocents from the West Australian bush, caught up in

the war’s mangled tactics and resultant carnage. The image of Archy’s body

reeling as the first of a barrage of bullets hits him has become emblematic of

a generation of youth laid waste by the Great War.

|

| Archy (Mark Lee) succumbs, final image from Peter Weir's Gallipoli. |

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old: Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn. At the going down of the sun and in the morning, we will remember them.

Says it in a nutshell…

But still I felt strangely detached. The world depicted in

‘Gallipoli’ was essentially one where fighting for Empire, macho stereotypes (both

benign and calculating), volunteering as adventure seeking and an affinity

between athleticism and soldiering prevailed. The tragedy was that these were

exploited not that there was something flawed in the very concepts. That was my

reading when I caustically dismissed the film as being about ‘a load of mates

mucking about in the desert on camels before getting their heads blown off’.

To my knowledge, no immediate relative of mine had served or

died in a war. There were no stories of awaiting telegrams with dread or

mourning war dead. No framed photographs

on the sideboard of young men in uniform who would never return. No

disoriented, damaged soldiers who did return but then stumbled trying to pick

up life with their families. Maybe that was why I couldn’t identify with the

Anzac personae in Weir’s movie or in much of the other Anzac mythology.

A dramatization of Charles Bean’s war journalism and diaries

I saw some time in the 90s began to tease out for me the disparate, paradoxical

threads of how the Anzac story has evolved. The production may have been called

‘The First Casualty’ in reference to US Senator Hiram Warren

Johnson’s 1918 remark about truth and war reporting, that would certainly have

been apt. Australian troops could be

almost insanely brave and they could also be culturally insensitive yobbos

wrecking Egyptian bordellos whilst contracting and spreading syphilis. What to

report to the folks back home? Not the full story that’s for sure. Probably not

until Vietnam, the war that came into our living rooms, was much quarter given

to the idea that the public might benefit from knowing the complex, confronting

fact that there are not simply ‘goodies’ and ‘baddies’ in a conflict.

I knew about the shell shock that afflicted

so many WW1 soldiers and had encountered stories about survivors of WW2 and the

Holocaust who never spoke of what they had experienced. In the aftermath of Vietnam and Afghanistan

our society began to understand more about post-traumatic stress disorder and since

the late 20th C there has been a growing acknowledgement of the

mental health impacts of war and the displacement, dispossession and

persecution that are part of war. In the last few decades we have begun to

welcome formerly excluded Vietnam veterans, women who served in the armed forces as nurses and the

descendants of Aboriginal diggers in Anzac Day marches. There have also been attempts

to look at the Gallipoli story from a Turkish perspective, like the 2015 film Gelibolu.

While April 25th is the

anniversary of a specific event, the connotations of Anzac Day are broadening

and the conflicting emotions I have always felt about the day are becoming

reconciled. There may still be beers and

two-up, but the day isn’t merely an opportunity for white blokes to hit the

grog and valorise amorphous ideas of mateship and their unexamined masculinity.

Along with this evolution, the discovery of two

great uncles, both Lance Corporals who served in the AIF in France during the Great

War, has brought a whole new personal dimension to Anzac Day for me. My husband’s

great uncle Howard Ricordi Gunderson was a locomotive fireman in Newcastle who

volunteered in 1915 at the age of 27. The records show that whilst on active

service he was treated for mumps, venereal disease, influenza and injuries

sustained in battle four times, the last unsuccessfully. He succumbed to his

wounds on 14 April 1918 and is buried in Ebblinghem Cemetery, France.

The correspondence between his brother Charles and mother Flo and the

British army trying to determine what his injuries were and to obtain

photographs of his gravesite makes for harrowing and poignant reading.

|

| Howard Gunderson's name listed amongst the WW1 casualties, National War Memorial |

My great Uncle Frederick Charles William Pittard

was luckier. He was 21 years old when he signed up at Warwick Farm in August

1915 recording his job as ’clerk’. He

trained at Victoria Barracks and embarked for France early in 1916. He suffered

at least two episodes of shell shock and was hospitalised for injuries five

times. During 1917 he enjoyed three months’ respite from battle, undertaking, then

delivering, training in England. He was repatriated to Australia with a serious

fracture to his right forearm in October 1919 and discharged from the army in January

1920.

Apparently Uncle Charlie, as he was known, had

reduced strength in his right arm for the rest of his life, but he returned to

clerical work, built a fine house in Harbord, stood for Council, administered

the annual Warringah Shire & Manly Agricultural & Horticultural Show

and fathered my first cousin once removed, Norma, before dying, grieved by both

his widow and his mistress at his funeral, in 1956 (the year I was born).

|

| Great Uncle Charlie, Frederick Charles William Pittard (1894-1956) |

The belated kindling of the Anzac spirit in

my bosom began with the discovery that great Uncle Charlie existed, that he was

a digger, with seeing him pictured in his uniform, reading his military file and

talking to his granddaughter, Diane, about her recollections of him. A sense of

personal connection began to form. Encountering

the Gunderson family, feeling their sense of pain and loss, tracking their

quest for more information about the cause of Howard’s death and for images of

where he lies, almost ten and a half thousand miles from home, did the rest.

| ||||

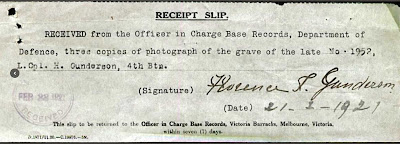

| Receipt signed by his mother for 3 photographs of Howard Ricordi Gunderson's grave at a cost of 3d each. |